| |

|

All

Saints, Wacton

|

|

This

big church sits in its pretty village less than a

mile from the town of Long Stratton's anonymous

suburbia, but still has a thoroughly rural

setting. The tower narrows considerably, and is

clearly in two stages, probably three. The lowest

stage is almost certainly Saxon. But the

church built against it is something quite

singular. The narrow graveyard accentuates the

sheerness of the walls, a long, tall, narrow nave

and chancel in one that is pretty much as it was

when rebuilt, on the eve of the Black Death. By

the later decades of the fourteenth century we

stopped building churches like this, and the

colder rationalism of Perpendicular would take

over from the mystery of Decorated. All Saints

captures the moment before this happens

beautifully. What would have happened if the

Black Death hadn't arrived? European architecture

fragments at this moment, and probably

Christianity would not have become such a serious

business. Something of the joy goes out of

European culture in the middle years of the

fourteenth century.

|

What is this building like inside? When I

first wrote an entry for it I answered my own question in

just two words: no idea. All Saints was well-known by

East Anglian church explorers for being pretty much

completely inaccessible. It was not popularly known as

Fortress Wacton for its looks alone. But, as Bob Dylan

was wont to observe from time to time, the times they

are a-changin', for I was excited to discover that

All Saints was taking part in the 2010 Open Churches

week. Peter and I hurried up the A12 and out into Long

Stratton's hinterland. The sign on the gate confirmed the

rumours, and we opened the door into - well, what do you

imagine?

I have noticed that often it is only the

dullest, most over-restored churches which are kept

locked from one Sunday to the next, but I can reassure

you that this is not the case with All Saints, Wacton,

for this is a fascinating and very lovely church, which

deserves to be so much better known than it is. The

lovely brick floors, the airy tracery of the screen, the

substantial 15th Century font which would not be out of

place in one of Norfolk's grand, urban late 15th Century

churches, all conspire to an interior which is rather

breathtaking, actually. I was pleased and excited to

discover it, and perhaps a little cross that other people

hadn't been allowed to explore it too. But taking part in

Open Churches week is a step in the right direction, and

I hoped it might encourage the parish to embrace the

radical idea of being open during the days of other weeks

as well.

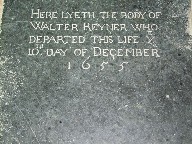

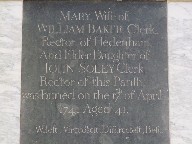

| There

are some intriguing ledger stones of the

Commonwealth period set in the brick floor around

the font. They are entirely secular except that

of the 26 year old John Eley who died in 1647 in

hope of resurrection unto life. Almost a

century later, a mural tablet remembers that Mary

Baker, daughter of the Rector was Wisest,

Virtuousest, Discreetest, Best. The mason

has had the grace to correct his spelling mistake

in the second word. Two

features were outstanding for me. One is the

roundel of 17th Century continental glass

depicting Christ with the Apostles, which I am

afraid is impossible to photograph because it is

in a perspex casing. The other is the excellent

1623 brass inscription to Abigail Sedley, the

daughter of John Knyvett of Ashwellthorpe - can

there be a more beautifully lettered brass of

that decade anywhere in Norfolk? At one time, it

would have been in the floor of the nave or

chancel. Now, it is screwed to the south wall,

and if there is ever a fire here it will melt

away like so much butter.

|

|

|

Simon Knott, February 2006

|

|

|