| |

|

St

Michael, Braydeston

|

|

And

so we came to Braydeston. It was the end of the

Historic Churches bike ride day 2007, and all

over England the welcomers were taking in the

sign boards, washing out the squash jugs and

putting the last of the biscuits back in the tin.

We had visited 19 churches so far; a modest

number, perhaps, on this day when virtually all

are open, but we had found the Anglicans of the

Yare Valley to be a particularly friendly bunch,

detaining us with their conversation and offers

of cups of tea. They seemed genuinely pleased to

see us, although this may well be because

ordinarily most of their churches are kept

locked, unlike the majority in Norfolk. We had seen

Braydeston off on its gentle hilltop several

times during the day, particularly from Blofield,

where the great tower is less than half a mile

from Braydeston's little boxy one. But that is as

the crow flies, or the rambler walks, or the 19th

century Rector plods on his horse from one Divine

Service to another. To get from one to the other

by car, it is necessary to go out along the

narrow, doglegging lanes between fields already

ploughed, a smell of earth and the gathering

coldness of a late summer afternoon.

|

Braydeston

is one of those churches that few people visit, I would

hazard a guess. It isn't particularly well-known for

anything historic or interesting, and the setting is so

lonely that it is unlikely too many pilgrims or strangers

turn up to rattle at its locked door in frustration.

We came

down the track and parked, and a nice lady came out to

the gate to welcome us. You could sense that she was one

of those stalwarts of rural churches. These are the

people who count the collection, make sure the gutters

are cleaned out, fill in the health and safety forms,

organise the flower rota, and so on. They are the reason

why some rural medieval churches look as if they have a

busy life, and yet others have been abandoned. It often

has little to do with the size of the village, or the

number of people in the congregation. Ultimately, it is

about the commitment of a small number of people. God

help their churches when they go.

As it

turned out, this energetic lady had also written the

guidebook, and was very knowledgeable about her building.

St Michael rides its gently sloping hillside like a great

ship, the chancel lifting out of the waves. There was

obviously once an aisle on the south side, and although

there is the ghost of a Norman window on the north side,

the church looks mostly the work of the 13th century. For

a moment, you might think the same of the rather stark

tower, but in fact it appears to be the result of a

bequest in the late 15th century.

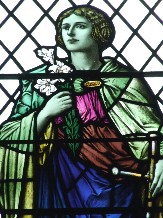

The

interior is rather narrow, and in the late afternoon

there was not much light getting inside. But the east

window, depicting Faith, Hope and Charity, is excellent,

and provides a lovely focus for worship. It was installed

as a war memorial in the 1920s.

There was

quite an early 19th century restoration here, and it is a

restrained one, most fitting in this quiet place. The

most unusual feature is the stumpy font; the top part is

an octagonal bowl in the Decorated style, probably on the

eve of the Black Death, but the pedestal is a huge thing,

as wide as the bowl. I couldn't make out if they were two

separate pieces of stone. Is it original, or was it added

later to replace a collonade?

The little

screen is delicately carved, and a beautiful pelican in

her piety plucks at her breast to feed her chicks with

her own blood. On the wall beside it is a reminder of

this building's preaching house days, the stand for the

hourglass which made sure ministers didn't skimp on the

sermon. The simplicity of the interior makes the few

details stand out, including the handful of memorials;

rather sad ones, I am afraid. One is to two of the sons

of the Reverend Thomas Drake, who, in 1830, were

drowned by the upsetting of a boat at Langley in this

neighbourhood. It seems that their father was

already dead, for this humble tablet to commemorate

the melancholy event is erected by Martha Stewart, relict

of the above. Further to the west is a reminder of a

tragedy of almost a century later. Walter Meire, the 25

year old son of Walter and Hannah Meire of Verne House in

Brundall, was killed in action at the Battle of Loos

in September 1915. His body was never found, and he is

remembered on the Loos memorial. A simple wooden plaque

remembers the two boys from the parish killed in World

War Two.

It was all

lovely and interesting, a real touchstone down the long

generations of the parish of Braydeston.

I stood

outside, and looked out across the rolling fields towards

Blofield's tower. This was the end of my fourth Historic

Churches bike ride day in Norfolk, and by chance it

happened that Braydeston was my 700th Norfolk church.

There will be many more to come, but so far it has been a

privilege to immerse myself in this great treasure house

of a county's faith and history, what the writer Simon

Jenkins has called the greatest folk museum in the world.

If we are in the last days of the Church of England - and

its demise has been greatly exaggerated, of course - what

will happen to these wonderful buildings? I thank God

that there is a greater will to preserve them than there

was in the 1960s, for example.

19th

century philosophers argued that Faith would die; but of

course, this hasn't happened, at least not yet. Many of

the Christian denominations are undergoing unprecedented

growth, and people are forever 'surprising a hunger in

themselves' to seek out holiness. And there are new

religions; consumerism, hedonism and humanism, to name

but three, which may seem evil in their ways to

Christians, but which are eagerly reached for by those

seeking to satisfy the emptiness in their lives. And what

of the future? As well as changing patterns within its

own sphere, Christianity is going to have to cope with

the emergence of popular scientific atheism as a real

threat. For the first time since the days of Communist

Russia and Nazi Germany, we regularly have philosophers

and psychologists appearing in the media to tell us that

our Faith is a form of mental illness, that bringing up

our youngsters in the Christian tradition is a form of

child abuse, and that the battle between good and evil

will be fought with genetics. God help us if these people

ever achieve political power.

Meditating

on this rather depressing development, I wondered what a

medieval Braydestoner would have seen if he had looked

out towards Blofield on a day like this, perhaps in the

early years of the 16th century. It would have looked

much the same, I suppose. There would have been fewer

trees, the fields would have been smaller, and there

would have been more people on them, for the annual

ploughing took far longer then than it does now.

What would

he have felt? The same cooling, evening breeze coming

from the east as me, perhaps. What would he have smelt?

the same sharpness of the cloven earth, the sweet

sourness of the leaves begining to turn, the year

beginning to wind down. And what would he have heard?

| It

was nearly six o'clock. I imagined the angelus

bell, which has not rung at Braydeston for almost

half a millennium, jangling out its brisk trot

across the fields, and the ploughing workers

pausing for a moment to stand - not in prayer

exactly, more in an attitude of meditation, a

moment to recollect who they really were, and

that there was more to life than ploughing and

sowing and reaping and birth and death and the

eternal struggle to survive. That they were, in

fact, God's People. And then

they would return to their work, shadowy figures

now in the deepening mist, as other distant bells

took up the call, further and more distant, all

the way across lost Catholic England.

|

|

|

|

|

|